The Strobe Image

Notes on the Photography of Gjon Mili

An Experiment

There are inventions and discoveries, rather special ones, which go far beyond their original function, which deviate and reach far beyond the domains they’re supposed to belong to, and acquire applications, not at all predicted or accounted for. What might begin as the response to a simple technical necessity, might very well end up being a complex and superabundant luxury.

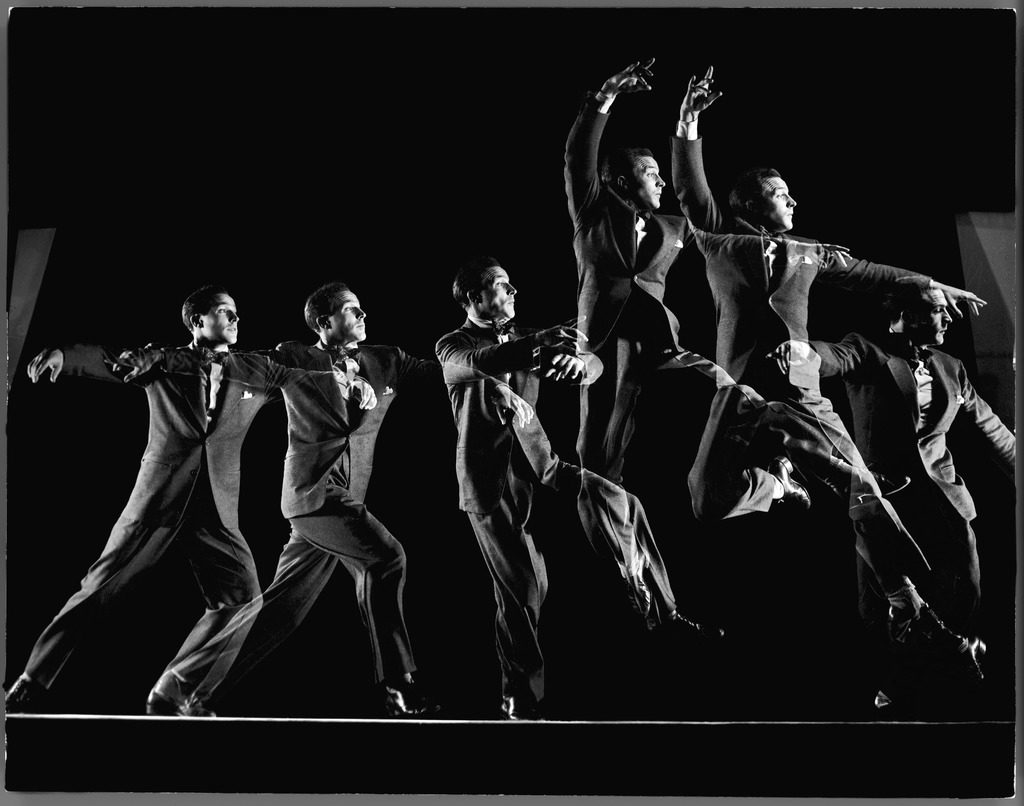

Such is the case of the stroboscope. Originally invented, and always serving as, a measuring instrument supposed to resolve purely technical problems in the domain of electronics and later even medicine, it acquired a very singular application in the domain of photography through the intervention of two proponents working together in the 1930s; Harold Edgerton and Gjon Mili. Their intervention was rather simple in character; it was nothing more than the transposition of an already existing stroboscopic mechanism to the camera. Technics becoming aesthetics. In its photographic application, it was the technique of using a rapidly flashing light inside a tube in order to capture the many instances which make up a movement and freeze them, condense them inside a single image.

Whether the objectives of this intervention were ‘’artistic’’ or merely experimental, designed to provide a visual supplement to its scientific and technical purpose ever since its beginning or not, is completely irrelevant. ‘’Don’t make me to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts. Only the facts.’’ stated Doc. What is much more worthy of notice is it’s making it possible for photography to escape from the immobile, and allow it to approach the limit of cinematic movement. I say limit, because the strobe image is not cinema, to which we are used to associate the moving image. Cinematic movement requires a horizontal unfolding of time, whereas, in the strobe image, time implodes. It is this implosion, a properly vertical distribution of time in the image, which is much more the fact of stroboscopy than any other technical specificity of its production.

The above is obviously not only true for the stroboscope technique, it is exactly what was happening with the chronophotographic experiments of Muybridge even earlier. However, the logic and experience of the two techniques are radically different. Chronophotography can be truly considered as proto-cinematic, inasmuch as the function of the photographs is to be ordered in a sequence which will reflect a horizontal unfolding of the stills to produce the effect of movement, of a movement which we have already seen and known in the mundane experience of everyday life. What happens in stroboscopy, on the other hand, is a rendering visible of what is essentially invisible (to paraphrase Paul Klee). I cannot hope to see the type of movement found there in my everyday life. Though there is nothing fantastical or imaginary about the objects of these photographs, the simultaneous rendering of still moments which make up continual movement remains to me invisible, even though I witnessed each of these stills.

The strobe image exists outside the technicalities of the camera which produces it. It is not an ‘’effect’’ of movement. The strobe image exists very well outside of the strobe photo. ‘’Nude Descending Down a Staircase no. 2’’ (Marcel Duchamp, 1937) is a perfect strobe image, and the strobe photo supposed to reproduce it (Gjon Mili, 1942) is one as well (though they are obviously not the same image.

The strobe image exists even in literature. ‘’The sun which does not come down and does not rise;’’, this image so beloved by Aragon and found multiple times in his writings, is it not the very epitome of quantum, stroboscopic movement?

The strobe image is not an ‘’effect’’, an artifice serving to simulate simultaneity. In observing such an image, I might even feel as if I am somewhere in between photographic stillness and cinematic movement. I am at the crossroads. What I experience in the strobe image is almost a contradiction, an obviously still figure always at the limit of movement, a perfect ‘’athletic immobility’’.

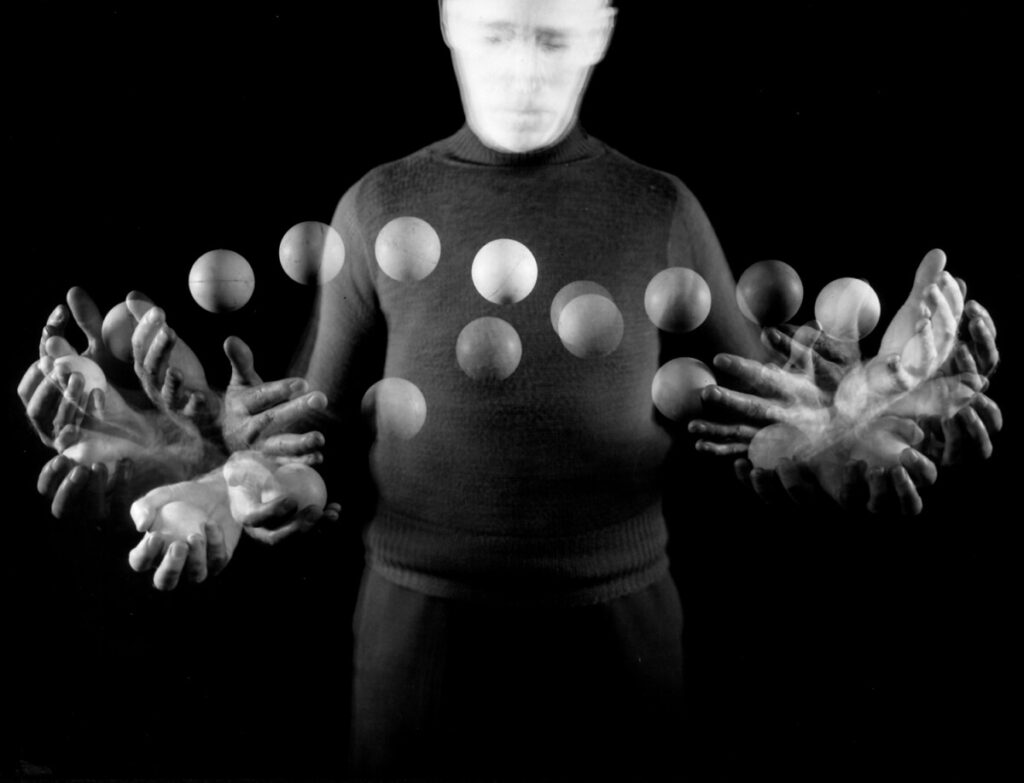

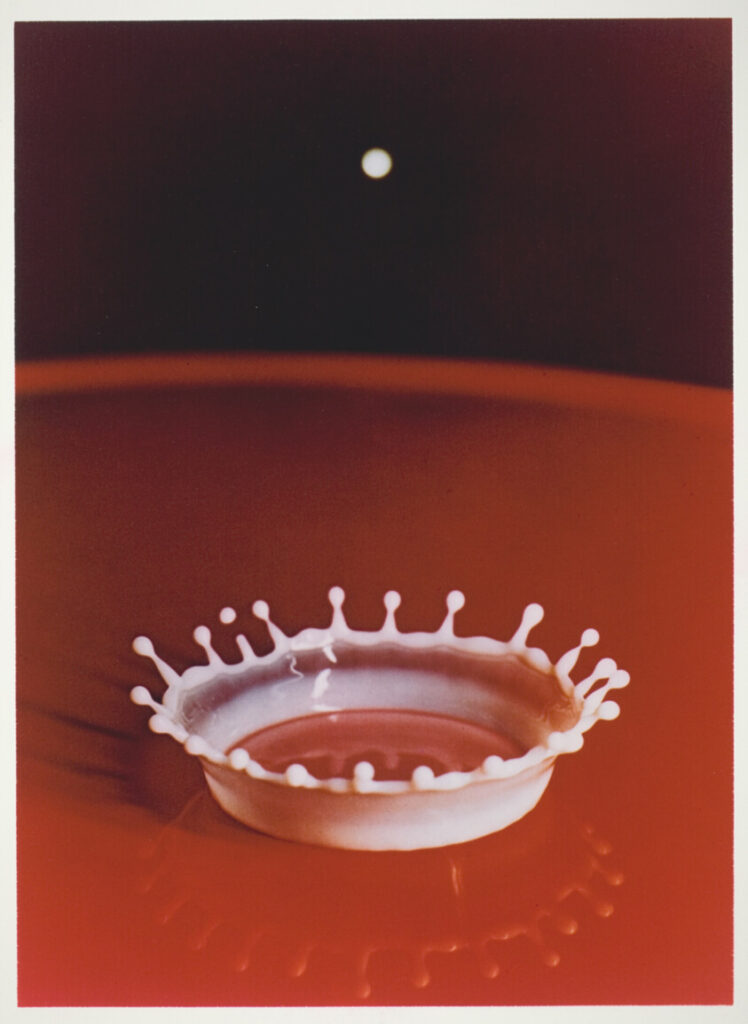

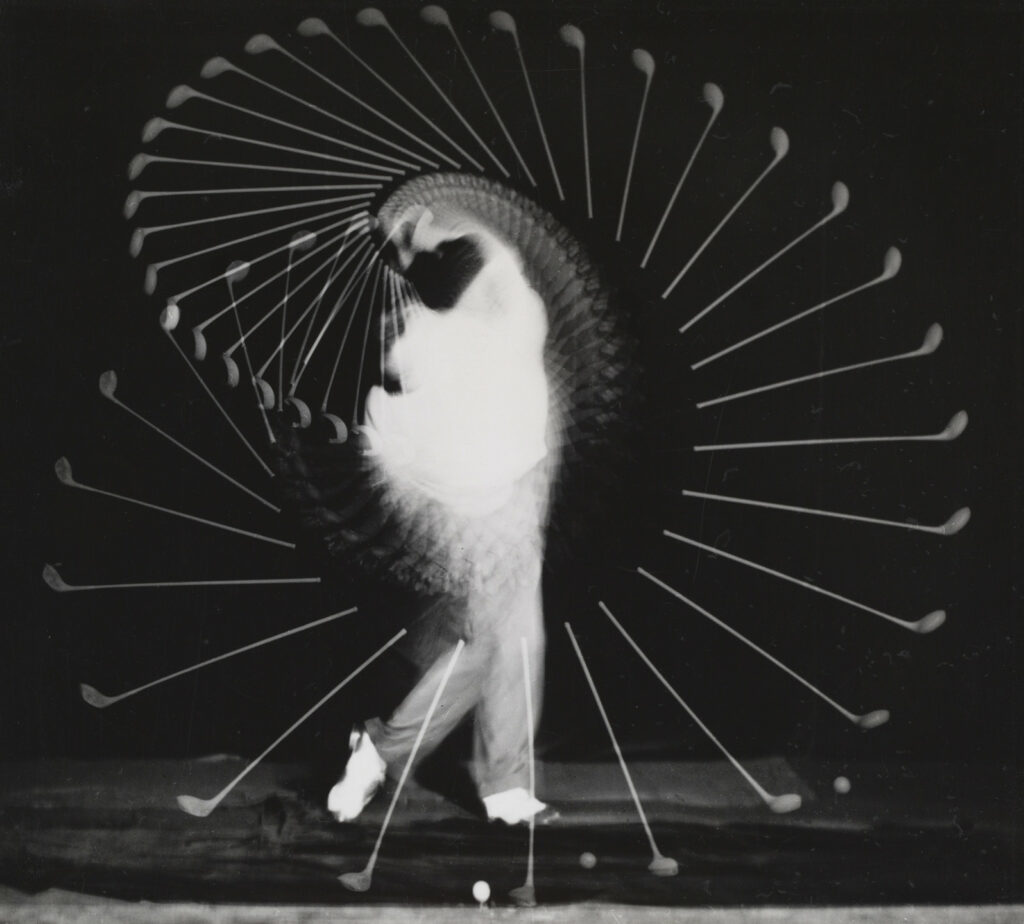

The strobe introduces a new mechanism, not only of making photographs but of fabricating objects, signs, and images within the photograph. A mechanism that shares a peculiar similarity with the literary one; that of fabricating completely new image-objects which do not belong to the ‘’real world’’. A pure example of such an image would be the Milk Crown of Harold Edgerton, fabricated from stills of drops of milk falling into a table and ultimately organized in a crown-like circle. Or, this image of the golf-swing ‘’carousel’’ by Edgerton.

Is it moving?

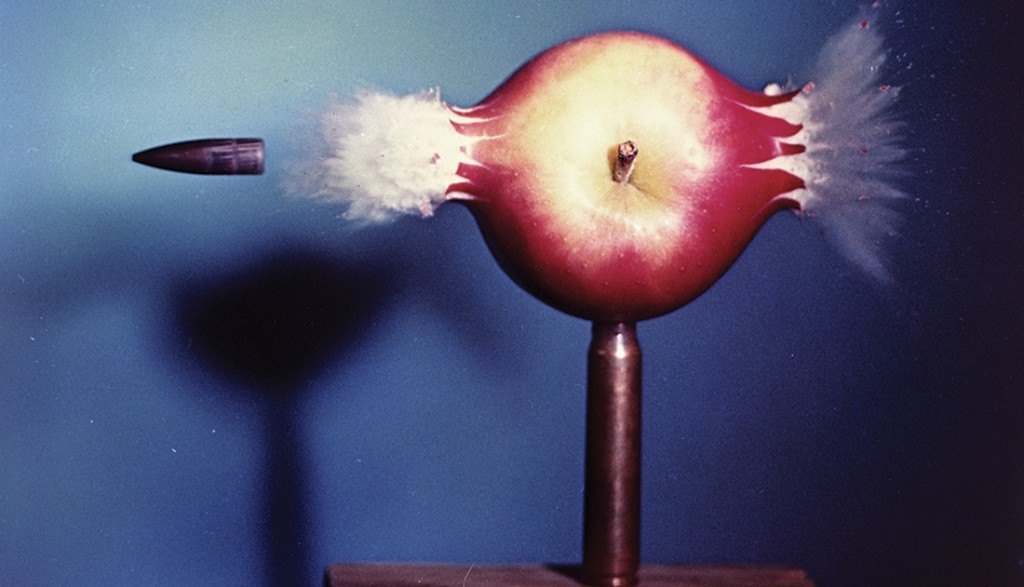

An object or person in a film moves, and it stands still on a photograph and painting – the usual way of speaking of these art-forms.

However, movement is not the privilege of the cinematic image. It might very well be expressed, implied even in ordinary photography. This implication requires a very peculiar approach to the object needed to be shown as moving. To imply a moving horse, it has always been customary in painting as well photography to show one foot on the ground and the other suspended in the air while galloping. The effect of movement in photography needs to be constituted through a logic that pertains to the real. I know the horse is moving in the photograph because it shares the properties of a moving horse I have seen in real life (foot on ground, foot on air). Thus, the fact that a photographed object is moving can be only implied. If we do not know how the object moves outside of the photograph, we cannot say that it is moving in the photograph. Indeed, according to the logic of images, the photo is always still.

The strobe image, however, is always in movement. I say in movement, and not moving, because neither the initial nor the final point of the movement is known, movement becomes a vortex of its own to which the object or figure producing it often remains completely peripheral.

Let’s analyze what is happening with the moving objects in these photographs. The above, non-strobe photos by Harold Edgerton, and below, strobe photos by Mili.

In the above photos by Hedgerton, we recognize the apple and the card, and more importantly, how these two behave when pierced or cut by another moving object. We recognize the bullet, the fact it moves, and how it can pierce or cut other objects. Movement is implied only once all of these extra-photographic facts come into play. Movement, as a sign, exists in these images, but it is not produced by them.

In the strobe image, on the other hand, the very repetition of the same objects in different sequential and periodic positions will immediately produce the sign of movement, and not the effect or implication. We do not see the object as if it were moving, but this movement is violently always already present; immanent, imminent, imploding.

Freezing Time

‘’Time could be truly made to stand still. Texture could be retained despite sudden violent movement.’’

Mili’s account of his own project is perhaps too technical, and we might as well go as far as saying that he did not fully understand the implications of what he was himself creating. Edgerton’s is almost exactly the same as well. Both try to describe what happens inside the image through the camera’s technical mechanism while producing it (‘’freezing’’ time). But the latter is in no way present or retained in the image it produces. Time is not frozen, for the object is in movement.

Nevertheless, it is not simply a misunderstanding. Mili’s account is the poetry of Science at its best; the manner in which all scientific development produces its own mythology (for it is never simply history) and traces its own ‘’progress’’.

‘’Revel, wonder and be amazed at what science has made possible!’’

It is not simply a question of simply embracing and rendering useful the innovation, one must remember it, look at it. This revelling upon technical progress is in perfect analogy with the religious experience of revelation. It is even a bit of ethics as well. One must constantly re-instate and re-enforce the scientific spirit within himself.

All this is already well known to all, science adores the glorification of its martyrs and saints. But what this usually amounts to, in our case, is a cold skepticism towards the sacred element of all artistic experience, a continual need to discredit all images which present themselves as too real, menacing, and properly sacred in their appearance. One can enjoy them, but they need to be banished from the domain of knowledge, we must speak of them as ‘’special effects’’.

– ‘’Remember that this image is only possible through the use of such and such technique, it is not mystery, it is not sacred, it is not real, do not let yourself be fooled!’’

The image seduces, the image is dangerous, the image is real.

The mechanics which govern movement in these images are not real!, they must not be accepted!.

The 21st Century man has an ever-increasing redundancy to let himself be deceived by the image, he is, rather, not schizoid enough. We are encouraged to enjoy the images produced by these techniques only for as long as we remember that they are produced through simple technical tricks.

The image is always real.

It’s moving

Obviously how this form of photography is made implies technically freezing the moving object in time through flash. The object moves from point A to point B in a particular time-span which corresponds to a particular way of dividing the movement and capturing it through flash in the strobe light.

However, there is something which is produced in the photograph which transforms the original movement which spawns it, the photographic result betrays the technical reality and conditions which made it possible and undergoes a sort of sublimation; a sublimation that has nothing to do with a distortion of desire, but one which simply transforms a reality, one which is always almost impossible to grasp, into an image, which, in itself, is always separated and somehow other than what I experience in the real world.

The trajectory of the object implodes, the time-span condenses. Time becomes vertical, diagonal even. Technically freezing the object and its movement through the strobe light will produce an image which in turn will unfreeze the movement when the latter is present in the image. The transformation of this freezed movement into an image is what transforms the movement itself, or, more precisely, the manner in which the movement is immanent to the object which emanates it. What stroboscopic photography makes possible is exactly the contrary of what its own creators said it was, it is the immense possibility of photography to capture movement and precisely that which is not freezed.

In these images of dancing figures, the dance is being carried out in the images themselves. We do not witness the dance as if we were present before it, the dance is already there. We already know the dance of ballerinas who know how to move from one point to the other, what is happening here is that all the positions the ballerini/a has traversed are dancing with each other. Here movement is not a secondary product of the dance, it’s what is dancing. If dance is known as the exuberant play of time and movement, the delicious loss of the position which was before, and the hopeful promise of the position that is to come, the strobe dance gives them all at once. Every position is dancing with the other, in short, it is quantum dance.

Hypertrophy: What happens with movement in this kind of photography, and maybe we can feel it that way just because it is photography, that is, an open invitation to interpret movement through a logic and sensibility which is proper to images rather than scientific facts and concepts, can be even advanced as the perfect visual critique of the traditional conceptions of movement; its understanding as the distance traversed by an object from point A to point B.

This is common to conceptions of movement formulated ever since Zeno of Elea1 up to the conceptions of modern physics before the discovery of quanta.

Movement in the images of Gjon Mili is pure quantum movement, and its time is pure quantum time. It is the daring leap of thought which allows itself the conception of the moving object as everywhere and nowhere in particular at the same time. Furthermore, it is the only possible way of visually demonstrating a state of the object which simultaneously moves on the one hand, and violently so, and rests perfectly immobile on the other.

_________________________

1 According to Zeno, one does not move even while he is moving; this corresponds perfectly to the mechanics of photographic movement. Diogene’s reply, that of mutely getting up and moving to a point nearby to ironically demonstrate the abstract absurdity of Zeno’s claim, corresponds to the mechanics of cinematic movement.

Great content! Keep up the good work!